Biography

The following sections have been developed using many formal and informal sources, including interviews of the author, diary entries, author reminiscences, and personal experiences of friends and family members. References have been cited and displayed wherever possible.

Childhood

Balivada Kantha Rao was born on 3 July 1927 to Suryanarayana and Ravanamma, in Madapam village on the banks of the Vamsadhaara river near Srikakulam town in Andhra Pradesh. He was the oldest of nine children. His father was the village primary school teacher with limited finances. Balivada studied in the village elementary school until he was nine. As he reminisced in one of his essays,

“I was born in a tiny village on the banks of the river Vamsadhaara in Srikakulam district of Andhra Pradesh and my first guru was my father. He was the headmaster of the village school and was well versed with our classics. He was a singer and performed in Puranic dramas in the village. My father, the river, the beautiful surroundings, and the people left an indelible influence on me”.

Read More...

When he was nine, he moved to Visakhapatnam to live with his maternal uncle and aunt. He enrolled in AVN College high school where he studied until 9th grade. As Balivada described his experiences in an interview:

“My aunt who lived in Visakhapatnam knew all the old stories. She narrated them to me and helped develop my interest in short stories. Later, in 8th standard I came in contact with the Principal, Shri Vankayala Venkatrao. He looked just like Pandit Nehru. The day after O’Dwyer was assassinated, he made us write an essay on the topic. He also got us to start a handwritten magazine, “Vidyarthi”. I was made the editor. I wrote an essay for this magazine which he liked. He even read my essay in the higher classes which was a tremendous source of encouragement for me.”

Moving back from Visakhapatnam to his village, he finally received his Senior School Certificate (SSLC) from Narasannapeta, a neighboring town. Later, he would fondly remember those days studying under the lone street light for his SSLC exam and riding a bicycle for about 9KM each way to high school and back. He managed to pass the exam with modest grades at best. To support his father, Balivada stopped further studies and took up a job with the Army Ordinance.

Back to Top

Career: Government Service and Early Writing

At seventeen, Balivada joined the Army Ordinance Depot as a temporary civilian clerk. After the war, the office was closed down and he had to go back to his village. This was in some ways the beginnings of Balivada the writer. According to him:

“In 1947, I spent some time in my village and read Kovvali and Jampana’s novels and had the yearning to write. I wrote a novel, Sarada. With some praise and encouragement from my aunt, I wrote to Raut Book Depot asking if they could publish. They responded in the negative stating that they don’t publish new authors. So I sent it to the magazine, Chitragupta. It was accepted and published in serial form. Later, I got a job and moved back to Visakhapatnam. I used to visit the Hindu Reading Room after work and read until they would close at night. I wanted to write for G.M. Acharya’s “Prajabandhu” magazine which published a single short story every week in the center page titled “This week’s story”. I wrote my first short story, Parivartana, and it was accepted and published in this magazine”

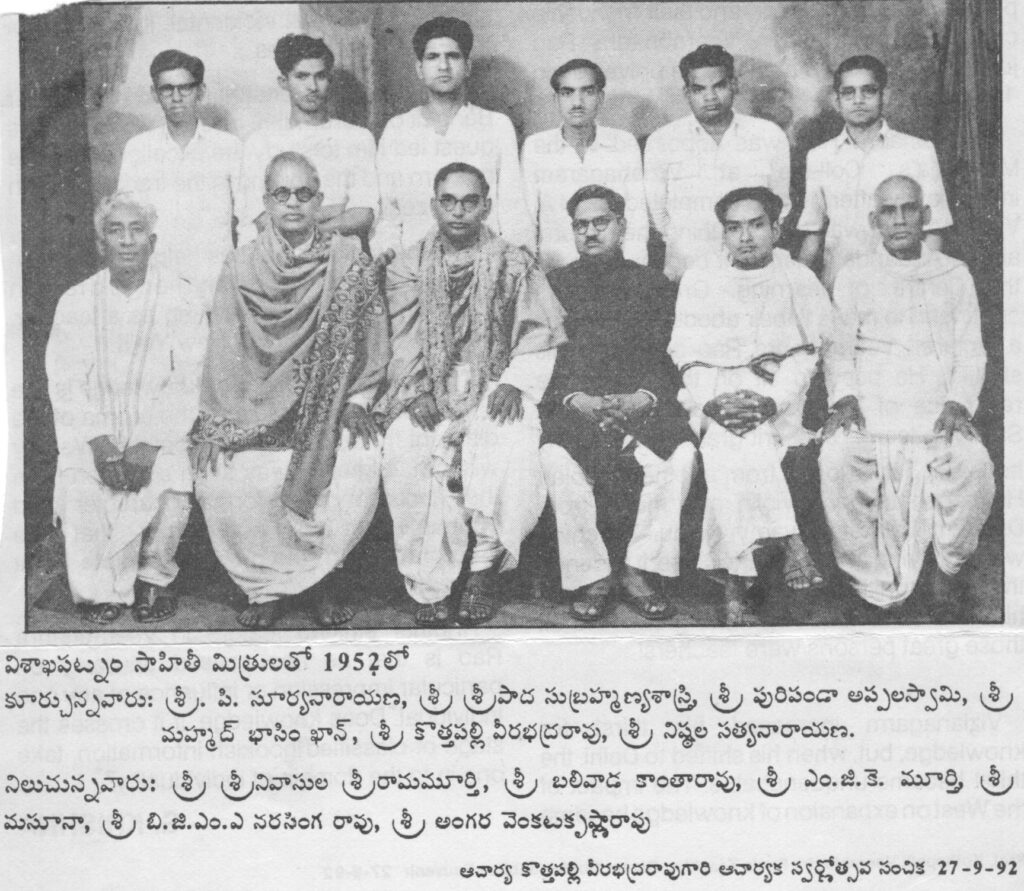

Read More...He went on to publish in Andhra Patrika (short story “Ammo”) and then the famous magazine, Bharati (short story “Nerasthudu”). He had finally arrived on the literary scene. On the literary environment and peers in those days in Visakhapatnam, he further states:

“From Lalit Kala Samiti, it transformed into the Writers Club. Shri Puripanda, Masuna, Kalipatnam, Angara Surya Rao, Angara Venkatakrishna Rao, Achyuta Rama Raju, Raavi Sastry, and Puranam Subrahmanya Sarma were all part of this club. The contact with all these writers provided the motivation and the encouragement to write.”

His early works were influenced by the Bengali writer Sarat. He states:

“When Annapurna was published in Bharati, a critic praised my work and commented that we see an emergence of a Sarat in these parts too. That’s when it struck me that I need to develop my own style. The novel, Godameeda Bomma (The picture on the wall) was the result“.

This novel was a milestone in his growth as a writer.

In his job, he steadily rose up in the organization by dint of his hard work and commitment. He spent many years in Visakhapatnam, Bombay, Delhi, and Vasco (Goa) with his family, making significant contributions in his job, as well as observing and learning the local history and lifestyle. His job also required him to undergo training and evaluation (including technical training although he was only a high school certificate) at various defense and civilian training institutes located all over India for which he would travel with colleagues. He would always make time from the demanding schedules to research and create exceptional ideas for short stories and novels. Novels like Matsyagandhi, Punyabhoomi, Delhi Majileelu, Ide Narakam Ide Swargam, Vamsadhaara, Love in Goa, and many short stories were a result of such efforts.

About Delhi Majileelu, he says:

“When I set foot in Delhi for the first time in 1969, this city felt very different from all the other cities I had lived in. Pandit Nehru was right in stating that every stone in Delhi speaks of its history. My novel can help in the understanding of the history, daily life, social, cultural, political, and economic aspects of the period between 1969 and 1974. I traveled every corner of Delhi during those five years, and also spent time researching in many libraries. In some sense, I almost worked as if it were my PhD research.“

He never viewed the lack of a college degree or a technical background as limitations in his job. He made it up with his hard work, innate curiosity, detailed research, note taking, and being open to feedback and criticism. These traits allowed him to successfully navigate a grueling year long technical training and evaluation at the age of fifty to enable his promotion to a Naval Armaments Supply Officer, a post from where he retired in 1985. He outlines the reasons for his success as follows:

“I get a lot of happiness from working hard. I believe in honesty, asking for help when I don’t know something, being committed to the work I have responsibility for, facing challenges with a positive and happy state of mind, and not worrying about results.”

He then goes on to add – “My job enabled me to work for the welfare of the employees. I took a primary role in setting up useful death benefit schemes, cooperative stores and credit society, co-operative house building society, and department canteen. This gave me immense satisfaction. From the perspective of a writer, I got a lot of exposure to their joys and sorrows.”

Back to Top

Critical Acclaim

His love for story-telling and capacity to write was such that he wrote consistently throughout his life. His known, documented output of novels, short-stories, and plays are captured in this list. Below is a description of some of his selected works as reviewed by critics and his contemporaries. You can read some of these novels and short story collections on the literature page.

Novels

In The Hindu article “Presenting a realistic panorama”, Chitrakavi Atreya writes

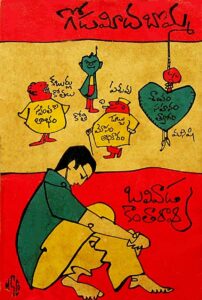

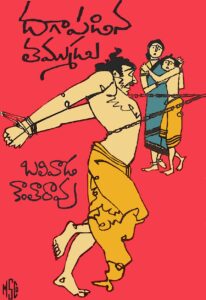

Read More...“In 1961 came his classic Dagapadina Tammudu (the deceived brother) which describes the paradox of declining happiness in the society as civilization advances. Pullayya, the native son of the soil leading a harmonious life falls a victim of village politics. The dispossession of land is only a prelude to the eventual disintegration of his life. His wife Neeli ends up as a beggar in the city. “The five elements – Sky, Land, Air, Water, and Fire adhere to their dharma. If man who is a compound of these elements discards dharma, then nothing can save him or the world”. In these words, a fellow convict sums up his belief to Pullayya, the deceived brother. This eternal truth is Balivada’s credo and keeps appearing in all his works.”

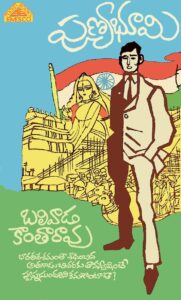

“Punyabhoomi (the holy land, 1972) is another classic. The story centers around Krishnamurthy, the only son of an Indian immigrant in London who wishes to revisit his mother land in a spirit of discovery. He visits Bombay and Calcutta besides his ancestral village and hometown in Andhra. He tries his hand at setting things right in society and stays back in India to help with national reconstruction by inculcating the values of service, sacrifice, humility, self respect and courage of conviction among the countryfolk.”

“His magnum opus is Vamsadhaara, which portrays the story of three generations, using the local dialect of Srikakulam for all the characters of the novel. An appreciable quality in Kantha Rao is, he described a problem in detail and also suggested the solution. The important characters in the novel, Jenikaiah, Kiriti, Sivaram, and Ratnamma empathise with and work for the uplift of the downtrodden – the dalits.”

“Sampangi depicts the life of a nautch girl who loves a man of her choice but ends up marrying another man under strange circumstances. Balivada describes the mental struggle and agony of Sampangi very admirably and makes the readers emphathize with Sampangi, who ultimately sacrifices her life. Kantha Rao is adept in depicting the family and societal life and eulogises the eternal values of love, sacrifice, and service. Karmabhoomi is a political satire which demonstrates his sincerity and steadfastness in sticking to convictions. His novelette Matsyagandhi is a powerful story of love, hatred, and sacrifice of the fishermen of a village near Mumbai”

Short Stories

In the Andhra Pradesh Times article “Spreading the fragrance of goodness”, Panduranga Rao writes:

“In 1969 Kantha Rao penned the story Mungisa (The mongoose) in which the pet mongoose, Bayanna, gifted by a grateful tribal to Dr Appa Rao in a village near river Vamsadhaara becomes a child of the house and drives away the rats and bandicoots. On a mistaken notion that this mongoose is a killer of his chicken, a ferocious neighbour, Bhairavayya ensnares and kills it when the doctor and family are away. While breathing its last, Bayanna folds his forelimbs and with an uplifted snout almost pleads with Bhairavayya to say – ‘No, I am not guilty. Please do not kill me’. Later when Bhairavayya comes to know know the real killer was someone else, the painful and appealing face of Bayanna haunts him.”

“Drushti written in 1991 has a young man, Ramesh, studying in America writing to his father on learning about the death of his grandfather – ‘Father, you taught me Shakespeare and Milton and how to live happily. Grandfather narrated stories from the Upanishads, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, and instilled in me the rudiments of the need for a vision to live as a human being. I am absorbing the thought, life, and culture of this land into the crucible of my own nation’s vision, given by grandpa, and when these two currents come into contact, a new spark may be born that shall light up my path.”

“This visionary writer lays much emphasis on stability of marriage and family relationships. His stories like Sankraminchena Sampada (wealth inherited), Yatra (a very evocative title meaning pilgrimage as well as traversing the path of life), and Tarajuvva portray his concern about these fundamental units of society’s stability. But Kantha Rao is no status quo jingoist who revels in the doormat model of Pativrata. In Yatra, Seshamma the calm wife of the shouting old man, Visweswarayya, says ever so confidently, ‘His anger has never won nor has my calm tasted defeat’. Sanyasamma in Paadulokam-Paadu Manushulu (A bad world and bad people) defies her father, gets educated and employed, forcing her father to change his opinion about women’s education. Padmavathi, to whom Bhushana Rao comes seeking marriage after the death of his first wife (in Rendu Roopalu) rejects him by saying ‘You could not respect a woman who bore you gem like children. Do you think I will have any regard for you?'”

“While this short story writer does not approve of the cult of violence in the name of ideology and progress, he has regard for those who lay down their lives in the cause of the welfare of the oppressed; it is this which makes him term these martyrs as Deva Dootalu (Messengers of God) and condemn all those that are in the service of a killer government as Rajadootalu (Representatives of Government) in the story by that name”

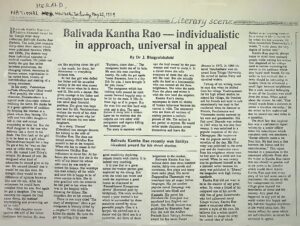

Dr. J Bhagyalakshmi in “Balivada Kantha Rao – individualistic in approach, universal in appeal“, writes:

“In the story Daanam (Donation), one stranger donates her kidney to the wife of Giridhar Rao. She does not accept money. Giridhar attends to her in the hospital. When she has to return to her hometown, he volunteers to escort her. She then reveals that she is the wife of his friend for whom Giridhar was once ready to donate his kidney. She worships this man silently all the while and is now happy to be of some service to him. She considers the attention he gives her as her reward.”

“It is true that the weak are exploited by the strong. But even the weak can retort as illustrated in Kannabhoomi Kanugonna throva (revealed path by birthplace). The story revolves around a poor woman’s hut which is surrounded by three mansions owned by powerful people. One is a lawyer, the second a doctor, and the third, a contractor. All three eye the poor woman’s land and want to usurp it. In a clever move, she tells them she will sell the land. But she actually sells the land to a businessman who can control all the three neighbours.”

Translated Works

Balivada’s novels and short stories have been translated into English and many Indian languages. Ide Narakam Ide Swargam has been translated into Hindi, Gujarati, and Odia. Sampangi has been translated into Hindi and Kannada. Dagapadina Tammudu has been translated and published by National Book Trust in all Indian languages. Mannutinna Manishi, Madanika, and Devulla Desam have been translated into Kannada. Matsyagandhi and Love in Goa have been translated into English. His best short stories have been translated into Hindi, English, and other regional Indian languages, brought out as collections of as part of anthologies. Some of these collections can be found in the literature page.

Awards

Balivada received many awards during his lifetime. One of his earliest awards was the Andhra Pradesh Sahitya Academy award for best novel in 1972 for Punyabhoomi. He then won the Telugu University best novel award for Vamsadhaara in 1986, the Gopichand literary award for excellence in modern literature in 1988, and the Venkata Sivaiah literary award in 1993. For outstanding contribution to Telugu literature, he received the Raavi Sastry (Rachakonda Viswanatha Sastry) memorial literary award, and the Kalasagar (Chennai) “Visistha Puraskaaram” in 1996. For his short story collection, “Balivada Kantha Rao Kathalu”, he received the Central Sahitya Akademi award in 1998.

Academic Research on Balivada’s work

Over the years, his literature has been the focus of Master’s and PhD level research. Dr. Yohan Babu received his PhD from Andhra University in 1989 on Balivada’s Novels. His doctoral research gives a very detailed view of Balivada’s novels and characters. This work and his work on detailed study of Vamsadhaara can be read here. In 1996, two PhD degrees were conferred for a critical study of Balivada’s short stories, and a comparative study of social reality in stories of Balivada Kantha Rao and noted Hindi writer Mohan Rakesh.

Many topics were researched for M.Phil (Master of Philosophy) degrees. Social aspects in his novel Vamsadhaara (in 1986), Women’s depiction in Balivada’s Novels (in 1995), and research study of Dagaapadina Tammudu (in 1992).

Some of his personal memories of his early years and the motivation for some of his work are captured in the two parts of the Q&A with Mr. Attaluri Narasimha Rao. These interviews give a very personal account of Balivada the person, and Balivada the writer.

Back to Top

Personal Life

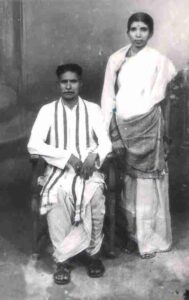

To Balivada, family was always a source of great strength. Early in life, he took over the responsibility of his siblings, cousins, and many of the extended family members, to get them educated, married, and oftentimes counsel them to get good jobs. In this endeavor, Balivada had admirable support from his wife, Sarada, whom he married in 1951. She was the charming and strong force behind many of Balivada’s initiatives for the extended family, and the public interface with friends. She too like Balivada, did not have the privilege of a college education.

Read More...

Sarada learned Telugu after her marriage, and became one of the strongest critics of his works. Balivada had the habit of reading out his writings for a quick review before sending it to publishers. In the early years, he relied on writer colleagues for the same. In later years, it was his wife who filled that role. Sarada, along with Balivada’s brother Narayana Rao, also made up for his poor handwriting by making fair copies of his manuscripts to send out for publication. As Balivada confessed about his writing habits:

“I cannot write at night. I write in the morning and finish a short story in one sitting. I don’t critic my work while writing. Before sending for publication, I usually read it to someone and make necessary modifications based on the discussion. My handwriting is very poor. My wife or my brother usually make a fair copy before I send it out”

After Balivada’s passing in the year 2000, Sarada took on the task of publishing some of his unpublished works – Ammi, Janmabhoomi, Maro Rajasekhara Charitra. She also brought out short story anthologies and reprints of many of his published novels until her passing in 2009.

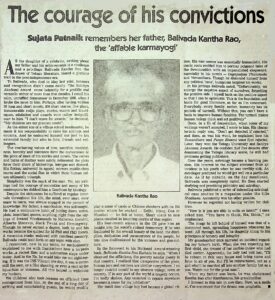

They are survived by three daughters, a son, five grandchildren, and three great- grand children. All his children are involved in promoting his literarure, including pursuing efforts to get his works translated and published. The eldest daughter, Usha, has been managing his literary collection and the interface with publishers and readers. In the article “Kalingandhrula gunde cheppulle nannagari kathalu” (My father’s stories are the pulse of North Coastal Andhra), she discusses his life and describes him as an unassuming, positive, and affectionate person, who despite his literary accomplishments and stature, was a great father. Their second daughter, Sujata, is a published writer in English. She has also translated some of his novels and short stories into English. In the Indian Express article “The Courage of his convictions“, she remembers her father as an “affable karmayogi”, and “We children took lessons on efficient time management from him. At the end of a long day of writing and entertaining guests, he would readily play a game of cards or Chinese checkers with us”.

She also adds, “Once, in a fit of desperation, when some of my writings were not accepted for publication, I wrote to him. His characteristic reply was, ‘don’t get dejected if rejected’.

Balivada’s youngest daughter, Kavita, and her husband DSV Gopikrishna, instituted a national literary award in Balivada’s name in telugu and support this along with their other charitable activities from the Bharatinidhi Foundation. Many emerging writers are being supported through this effort.

Their son, Ashok, has been involved in publishing any unpublished works, and most recently in the digitization and preservation of Balivada’s works.

Other interesting facts

Balivada was a voracious reader. Besides telugu, he read a lot western writers like Herman Hesse, Tolstoy, Anatole France, Mark Twain. He was a compulsive note taker and had many diaries of notes. For someone who studied in the Telugu medium, with English as a second language, all his note taking of his story plots were in English!

He had a strong interest and love for Astrology and Palmistry. According to him, “In 1955 I fell terribly ill. Swami Adarshnath came to see me and looked at my horoscope. He predicted that I would get back to work by July 29th. I got better and joined work much earlier. As I was feeling restless, I had to go back to my village. Finally I was able to join back at work on July 29th. That raised a question in my head, how was he able to predict so accurately? Surely there must be some merit to this approach. I started studying this myself. Astrology is quite an exciting topic.” He wrote a series of articles and stories based on Astrology which were published as “Shodhana“. True to his beliefs, these stories emphasized the power of human effort for outcomes.

He had a very infectious and childlike curiosity about everything. When his son shipped an encyclopaedia set from the US for his young nephew, Balivada got excited and went through many topics related to science and computers and made detailed notes in his diaries.

He wrote most of the time sitting on a chair, next to a wooden storage box that was a makeshift table, with the manuscript book resting on a writing pad. He would sit at his humble writing corner for hours at a stretch, sometimes finishing a story in one sitting.

Back to Top

Life Journey in his words…..

In the writers meet the day after the Sahitya Akademi awards ceremony in February 1999, Balivada summarized his life journey in a speech to the distinguished audience, reproduced here from his draft.

“A writer creates out of his life’s experiences. No wonder the famous Italian writer Alberto Moravia said…. “Over half a century, all I have done under the mask of different stories, is to tell the story of the life of a man called Alberto Moravia“. In my fifty years of literary career, perhaps I did the same. I am the product of the past, producing the fruits with my labor and leaving the seeds for the future. I am always reminded of Victor Hugo who said, “If the writer writes only for the present, let him throw away his pen“.

My roots are in my village and this helped me depict the lives of the deprived and downtrodden in my novels and short stories. I was born in a tiny village on the banks of the river Vamsadhaara in Srikakulam district of Andhra Pradesh and my first guru was my father. He was the headmaster of the village school and was well versed with our classics. He was a singer and performed in Puranic dramas in the village. My father, the river, the beautiful surroundings, and the people left an indelible influence on me. After my secondary school education, being the eldest child, I decided to help my father in managing his family of nine children.

Read More...I joined the Army Ordinance Depot at Visakhapatnam as an extra temporary civilian clerk when I was barely seventeen. After the war, the depot was closed and I went back to my village. Though I lost a temporary job, I gained a permanent work culture. I could not stay idle in my village so I started reading. I wrote my first work of fiction – a novel titled “Sarada” depicting freedom struggle. This was serialized in a popular fortnightly magazine, Chitragupta in 1947-48. The editor advertised this launch with the headline – “a novel by a very efficient writer”. My first short story was published in 1948. I never looked back from then and have since been able to write and publish 38 novels and around 350 short stories.

In the process of writing I had to face two enemies of creation – imitation and repetition of themes. Pandit Nehru rightly reminded us – “Art is life, neither repetition, nor imitation”. In my early work, someone commented that my short novel, Annapurna, reminded him of the famous Bengali writer Sarat Chandra Chatterjee. I became restive and delberately tried to evolve my own voice and a distinct style. When I found success in my own style of writing, I indulged in philosophical discussions in my fiction. A critic pointed out – “We expect from this author, a story book, and not a book on philosophy”. This altered my thought process and I earnestly tried not to lecture the audience.

I found gurus not only in the great masters of the past, but also in the ordinary people living around me. The Ramayana and the Mahabharata have been the most influential. The great telugu play Kanyasulkam by Gurajada Appa Rao, the forerunner of modern fiction, influenced my language. Some of the Russian, French, and English Masters of fiction also influenced me. Dostovyesky said, “I write about the very depths of human soul”, perhaps this is the ultimate aim of any writer.

The magic of the village ballad singer Ramaswamy, in keeping his audience glued, told me that whatever I say has to be said in an attractive way. In Visakhapatnam, when there was a bitter quarrel between two families, I saw the brother of one of the parties staying aloof. From him I learnt that, a writer should stand apart from the issue so as to be an impartial judge. From the confidential report of an officer, I understood that brevity is another hallmark of effective writing.

I was lucky in serving the Naval Armament Organization as it gave me an opportunity to see my country from Simla to Kanyakumari, and from Calcutta to Dwarka. I lived in cities like Bombay, Delhi, Vasco-da-gama. I loved these places, the peoples, and the environs. My novels cover the life of the Kolis in Mumbai, life in modern day as well as the past in Goa, and Delhi right from the days of the Indraprastha up until Pandit Nehru. I have been lucky to witness one of the greatest events in the history of my country – our independence. I was able to record the changing faces of our society, not as I saw it, but as I thought of it. Through my literature, I feel I revealed my philosophy of life for the future. I am proud to be an Indian, and proud to be a writer.

In my wanderings, I met lots of people who I respect even today. As a boy, I used to think my village was heaven. With the education I acquired in the town, I tried to understand my days in the village. After I traveled the country, I tried to see my village, town, and state through the windows from outside. In 1992, I spent some time in the US and understood their life, noticed many admirable qualities in the people, and noticed many issues common to our countries. Now, I feel hurt if something undesirable happens anywhere in the world.

To transform me from a village lad to one having a universal outlook, many people and many incidents helped me. I cherish these values and will continue to pen until I have energy left in me………….”

Back to Top

References

Q&A with Attaluri Narasimha Rao …Part I

( Published in Andhra Jyoti Magazine (1989) in Telugu. Translated into Hindi by Dr. J.L. Reddy. Translated into English by Ashok Balivada). We have not been able to secure the original telugu version.

Q: When did you first come to Visakhapatnam and why?

A: In 1936. To study in 5th Standard in AVN College’s High School.

Read More...Q: What was Visakhapatnam’s influence on you as a student?

A: My aunt who lived in Visakhapatnam knew all the old stories. She narrated them to me and helped develop my interest in short stories. Later, in 8th standard I came in contact with the Principal, Shri Vankayal Venkatrao. He looked just like Pandit Nehru. The day after O’Dwyer was assassinated, he made us write an essay on the topic. He also got us to start a handwritten magazine, “Vidyarthi”. I was made the editor. I wrote an essay for this magazine which he liked. He even read my essay in the higher classes which was a tremendous source of encouragement for me. In 9th standard, our telugu teacher, Shri Ramamurthy, came into class with our graded exam papers. He picked three of them and stated they all had model answers. He then picked up my answer sheet and kissed it since I had scored the highest. Of course it was a matter of great pride for me.

Q: Early on, did you ever think you would become a writer?

A: I had the obsession to write. But I never imagined I would write this way and become a writer.

Q: Under what circumstances did you first get involved with writing?

A: In 1947, I spent some time in my village and read Kovvali and Jampana’s novels and had the yearning to write. I wrote a novel, “Sarada”. With some praise and encouragement from my aunt, I wrote to Raut Book Depot asking if they could publish. They responded in the negative stating that they don’t publish new authors. So I sent it to the magazine, “Chitragupt”. It was accepted and published in serial form. Later, I got a job and moved back to Visakhapatnam. I used to visit the Hindu Reading Room after work and read until they would close at night. I wanted to write for G.M. Acharya’s “Prajabandhu” magazine which published a single short story every week in the center page titled “This week’s story”. I wrote my first short story, “Parivartan” and it was accepted and published in this magazine. I shared my excitement of having published my first novel and first short story with every cat or creature on the street! Today, you don’t find either.

Q: What are you views today about your first novel?

A: I laugh about it now. It had the influences of Kovvali, Jampana, the novel “Narayanarao”, and the Congress protest. But it still was a first step for me.

Q: You probably had the desire to get published in “Bharati”?

A: I used to think you cannot be a writer without getting published in Bharati. I sent my story, “Ammo”, but they published in “Andhra Patrika”. Then I sent “Nerasthudu” to Andhra Patrika, but it got published as my first story in Bharati.

Q: You also wrote some for the Ugadi issue of Andhra Patrika?

A: One day in the Reading room, I met for the first time a writer who had found fame. I felt he looked down upon me. I directed my disgust towards writing a story and sending it to the Ugadi issue of the magazine. My story was published but his wasn’t. I received twenty rupees for the story which turned out to be helpful for medicines for a friend’s wife.

Q: Your early writings seem to have the influence of the writer Sarat. What are your views on this?

A: Sarat’s literature was easily available in the Reading room. The others weren’t available. So I wanted to write like Sarat. “Parajaya” and “Annapurna” has Sarat’s influence.

Q: How did you come out of that influence?

A: When “Annapurna” was published in Bharati, a critic praised my work and commented that we see an emergence of a Sarat in these parts too. That’s when it struck me that I need to develop my own style. The novel, “Godameeda Bomma” (The picture on the wall) was the result.

Q: This novel made you quite famous, correct?

A: The novel was published after being widely advertised for 3 months. When I was writing this novel, Shri Puranam (Subramanya Sarma) was here. One day he said, “One more Gurajada has evolved in our region”. That was a big compliment, but I also wondered if I could ever reach that level. I dedicated myself to making a sincere effort and the result was “Dagapadina Tammuda” and “Vamsadhara”. To this day, Puranam’s statement continues to motivate me.

Q: You were associated with the writer’s club in Visakhapatnam from the early days. What was the literary environment like in those days?

A: From Lalit Kala Samiti, it transformed into the Writers Club. Shri Puripanda, Masuna, Kalipatnam, Angara Surya Rao, Angara Venkatakrishna Rao, Achyuta Rama Raju, Raavi Sastry, and Puranam (for sometime), were all part of this club. The contact with all these writers provided the motivation and the encouragement to write.

Q: When did you first meet Shri Raavi Sastry?

A: My brother used to know him, but at that time I didn’t know that he used to write. Bharati used to publish stories by him under the pen name, Jasmin. It was only after his story, “Alpajeevi” was published that I got a chance to meet him. By that time, he had joined the Writers Club in Visakhapatnam.

Q: What are your writing habits?

A: I cannot write at night. I write in the morning and finish a short story in one sitting. I don’t critic my work while writing. Before sending for publication, I usually read it to someone and make necessary modifications based on the discussion. My handwriting is very poor. My wife or my brother usually make a fair copy before I send it out.

Q: Who are your favorite authors?

A: I like Potana and Vemana’s poems. After becoming a writer myself, I have been especially attracted to the writings of Raavi Sastry and Kalipatnam Ramarao. From non-telugu writings, I like Herman Hesse, Anatole France, Tolstoy, and Mark Twain.

Q: Is there a single story or novel that you really liked and still remember?

A: Padmaraju’s short story Eduruchusina Muhurtham, and Raavi Sastry’s novel Alpajeevi.

Q: Which one of your own stories do you like best?

A: Pelli (Marriage). This has been translated into Kannada as well.

Q: Which of your own novels do you like best? For which novel have you received the most appreciation from readers?

A: Vamsadhaara and Dagapadina Tammudu.

Q: Your favorite film?

A: Apur Sansar. Among telugu films, Swarga Seema. I watched this film twelve times, including two back-to-back shows on the same day. I used to sing the songs and deliver the dialogs. I was asked by a Punjabi officer for a recommendation of Telugu songs. I gave him the record album for Swarga Seema. He liked it so much that he ended up listening to it until the record got ruined!

Q: Your favorite singer is?

A: Bhanumati. I still listen to her songs to lift my spirits whenever I’m in a low mood.

Q: What are the reasons for your success in your job?

A: I get a lot of happiness from working hard. I believe in honesty, asking for help when I don’t know something, being committed to the work I have responsibility for, facing challenges with a positive and happy state of mind, and not worrying about results – these are some of my reasons for a successful career.

Q: Can you talk about the various schemes and projects you were associated with as an officer for the welfare of the office staff and employees?

A: My job enabled me to work for the welfare of the employees. I took a primary role in setting up useful death benefit schemes, cooperative credit society, co-operative stores, co-operative house building society, and department canteen. This gave me immense satisfaction. From the perspective of a writer, I got a lot of exposure to their joys and sorrows.

Q: Astrology and Palmistry are your hobbies. Which of these is dearer to you and how did you get interested in these?

A: Astrology. In 1955 I fell terribly ill. Swami Adarshnath came to see me and looked at my horoscope. He predicted that I would get back to work by July 29th. I got better and joined work much earlier. But due to some restlessness, I had to go back to my village. Finally I was able to join back at work on July 29th. That raised a question in my head, how was he able to predict so accurately? Surely there must be some merit to this approach. I started studying this myself. Astrology is quite an exciting topic.

Q: Going forward, what activities will keep you occupied?

A: Writing is like a drug for me. I will keep writing until I have the energy and the strength. I would like to write a novel about the industry. Secondly, I want to write a novel based on the cultural history of the Buddhist period.

Q: Until now, what life truths have you found?

A: With all the ebbs and flows in life, no one can stop you from getting what ought to be yours. I don’t accept the statement “I don’t have time” from anyone. One has to make time. Tomorrow’s work should be done today because only today belongs to us. To lead a peaceful and comfortable life, some level of neutrality is important. Unless we demonstrate affinity and love towards others, we cannot expect to receive these from others.

Back to Top

Q&A with Attaluri Narasimha Rao …. Part II

(Published in Andhra Jyoti Magazine in Telugu, 11th Dec, 1989. Translated into Hindi by Dr. J.L. Reddy. Translated into English by Ashok Balivada). We have not been able to secure the original telugu version of this interview.

Q: Looking at your novels, the plot and characters of one novel never appear in another. What are the reasons for creating such diversity of plots and characters?

Read More...A: We cannot create from nothing. Artwork is created when a rock or gold is transformed into a sculpture or jewelry. Similarly, a writer needs to search for the raw material for his art from the people around him. A novel is created when a writer combines what he sees and hears around him with his own personal experiences. I have been to many places, met a variety of people, and faced many situations. I believe these experiences have helped create the diversity of plots and characters in my novels.

Q: I am eager to know how some of your novels sprouted from these experiences. In the early days, you got a lot of fame from Annapurna which was published in Bharati…..

A: Yes. It was published in 1950. Shri Banda and Shri Kuppili Venkateswar Rao (note: Both stage and cinema actors of repute in those days) made this into a radio play as well. This was republished in Bharati in 1985.

Q: Through Annapurna’s ideal character, you demonstrated how she calms the turbulence in her younger brother’s life with love, sensitivity, and understanding. Did you meet such a sister in real life?

A: I had a friend. He narrated how his sister-in-law was trying to create turbulence in their lives. He had the responsibility to get his sisters educated and married. There was a huge demand for family oriented novels in those days. If I had portrayed the sister-in-law as a strict and difficult character, it would have been problematic. I created Annapurna as an ideal character with a hope that my friend’s sister-in-law would read this book and change for the better.

Q: It felt you were leaning towards the literary style of Sarat. Which work of yours brought you out of that influence?

A: I used to read a lot of Sarat in those days. I still feel Annapurna is a character from Andhra.

Q: Just as a comparison, which other literature have you read?

A: As a writer, I had to dish out a variety of tastes to my readers, right? Hence I couldn’t make do with just one type of dish. Unless a writer believes in “Let noble thoughts come from all sides”, he or she cannot learn anything. That which cannot be learned, cannot be made. Whichever book I could lay my hands on, I read, including telugu translations of Hindi writers. My novel Godameeda Bomma (The picture on the wall) was an attempt to come out of the effects of all these reading and influences. In those days, translated novels used to get published. In such circumstances, Godameeda Bomma was advertised for 3 months before being serialized in Andhra Patrika. This was also adapted as a radio play by Shri Hitasri.

Q: I still remember Venkatarao talking into the air. How did you create such a character for this novel?

A: I had a colleague at work. Listening to him made me laugh a lot. Its difficult to imagine this situation and write. In those days, I was trying to write Godameeda Bomma (The picture on the wall). So I asked him if he would have any reservations if I created a character based on him and named him Subbarao. With a grim face, he said, “I do have reservations. The only way I can stay alive in that character is if he has my name. I will have no reservations if you create this character with my name”. Its been thirty years since my colleague passed away, but you still remember the character based on him. Clearly, his wish has been fulfilled.

Q: After this novel, you published Dagapadina Tammudu (Cheated younger brother). In the 8th chapter, you created the character of blind Venkanna. That was very pathetic.

A: Shri Bomman Viswanatham mentioned that he cried all night while translating that chapter into Bengali.

Q: Recently, in the context of Telugu literary novels, Shri R.S. Sudarshanam wrote, “The character of Neeli stands out like a jewel among all the women characters created in this decade”. Can you tell us the circumstances behind creating characters like Venkanna and Neeli?

A: Through his writing, a writer tries to create his own magic, correct? There’s a small difference though. Magic disappears from your mind in a short time, but great writing leaves an indelible impression. It throws the reader into raptures. It can aid in their transformation. I had personally seen the post war conditions very closely. The characters of Venkanna and Neeli may have played a part in one critic’s statement about this novel – “Without leaving anything to imagination, life has been presented in a simple, clear, as is, and honest manner”. There was a blind person in my village. Similarly, Neelamma was called Neeli. She was dusky and very beautiful. But I can’t say my characters were completely based on them.

Q: Your readers remember your novel, Sampangi very well. It was serialized in 1968 in Andhra Prabha with Bapu’s colorful art. It also received appreciation as a radio play. It has been translated into Hindi and Kannada. Filled with sorrow, what was the story behind this novel that flowed like a love song?

A: I was visiting my village from Bombay for my brother’s wedding. There was a ruined well behind our house. Sitting on a rock and staring at the well, I felt the urge to write a story. As I delved deeper, I discovered the well had its own history. People mentioned there was a flower garden around it. The flowers not only adorned the hair of women, but also spread on their beds. As I reviewed my grand uncle’s life, I got the raw material for the character of Narahari. The reason to portray Sampangi’s character as a goddess of beauty – just my imagination of a beautiful lady who captivated my mind.

Q: You got a lot of fame from your novel Ide Narakam, Ide Swargam (This is Hell, this is Heaven). These have also been translated into Hindi and English. The Hindi translation (Gira Anayan Nayan Binu Baani) along with Premchand’s Sevasadan was a prescribed text book. You imagined yourself as a visually impaired person and wrote the entire novel. How was this made possible?

A: While living in Delhi, I met this gentleman at a friend’s house. I wanted to write a novel based on him. As I interacted with him, many ideas started developing in my mind. After writing my novel, I read it out to him and made many improvements based on his suggestions.

Q: What were you trying to convey in this novel?

A: We use the friendship and love of many people to make progress in our lives. But we seldom provide friendship and love to others.

Q: So why did you title the novel Ide Narakam, Ide Swargam?

A: He was born blind. Music was his wealth. Out of sheer helplessness, he gets married to a mute person. He was afraid that his children would be either blind or mute. But he gets to see the world with his son’s eyes. At that moment, he feels enlightened – For human beings, the only place of shelter is on this earth. This is hell and this is heaven. This is not the world of magical dwarfs that I once imagined. This is the only earth for us humans. This life is only mine. If I can understand the people and the incidents around me with a feeling of belonging, then even if I do not have eyes, I can still see.

This is the reason for the title.

Q: In your novels, one doesn’t come across characters that rebel against existing beliefs and circumstances. What is the reason for this?

A: Not every writer has the courage to write about rejecting existing beliefs and way of life. A person who demolishes a building because it is not useful, should have the courage to build a new one in its place. Another thing – a writer does not enjoy the right or freedom to do everything. There are limits to the freedom he enjoys. I believe a writer is like an expert mason. He cannot completely build the entire wall in his lifetime. He should work in a manner such that subsequent generations can continue to build on top of his construction. Instead if they are unhappy and bring down this wall and start from the foundation again…..the writer will perish within his lifetime. This responsibility is what makes the writer obligated to lay his bricks over the existing ones. This excessive caution is probably the reason why I did not create rebellious characters in my novels.

Q: In your novel Vamsadhaara, through the character of Ramdas, you nevertheless showed the dirt and squalor in society. About this novel that illustrates three generations of social life, noted writer Bharago (Bhamidipati Ramagopalam) wrote recently that it describes incidents that challenge your intellect as well as deeply touch your heart. He goes on to state that the regional dialect used is especially very authentic, and that this novel should be placed in the ranks of telugu classics like Malapalli and Veyipadagalu. How did you manage to write using the idiomatic expressions of the region even though your job required you to spend a greater part of your time in various parts of the country?

A: I used to take time off from work and spent time among the people of the region to make their acquaintance. Gradually I understood the colloquial language of Srikakulam and expressed it through various characters like Parayya and Gangamma. This dialect is slowly disappearing.

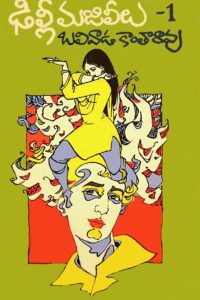

Q: In Delhi Majalilu, you covered the history and culture of Delhi from Yudhisthir’s Indraprastha until Nehru’s modern Delhi in over 500 pages. What inspired you to write this? What type of effort did you have to put in?

A: When I set foot in Delhi for the first time in 1969, this city felt very different from all the other cities I had lived in. Pandit Nehru was right in stating that every stone in Delhi speaks of its history. My novel can help in the understanding of the history, daily life, social, cultural, political, and economic aspects on the period between 1969 and 1974. I traveled every corner of Delhi during those five years, and also spent time researching in many libraries. In some sense, I almost worked as if it were my PhD research. Sadly, neither readers nor critics showed any attention to this work.

Q: You recently wrote two short novels, Ajanta and Ellora. What was the motivation behind writing these novels?

A: Before visiting any place, I try to gather as much information as possible. So, after reading about its history, construction, and mural artwork, I visited Ajanta and Ellora. Ajanta is like a school of art, while Ellora’s Kailash temple is a rare work of architecture. In this novel, I covered the 7th century CE when Buddhism re-emerged and the Kailash temple was built. Based on circumstances that prevailed during that period, I wrote this fictional novel.

Q: In Ajanta, the artist Aryadev says, “Art has no end. No art is ever complete. Try to understand the limitations in my art….and refine yours”. Similarly, towards the end you write that after creating man, God says, “My son, for your life on earth, I created an incomplete home. Understand its deficiencies….improve them….refine them”. This probably is your message?

A: No no. If you think this is my message, I would have failed as a writer. Only when the reader can form ideas and opinions of his own based on things I have written, would I assume any significance as a writer.

Q: You must be reading the novels being serialized in today’s magazines. Do you think the novel in literature is losing significance?

A: According to Pulitzer prize winning American writer, John Updike, not many in America are reading fiction in magazines, resulting in closure of many such publications. In our country, how many people can afford to buy magazines? Only a few libraries can buy them. These publications cannot survive unless the writing is tailored to the tastes of the reader. Updike further says, we do not have the internal strength to bear the pain resulting from our dreams. This is why fiction and story-telling is on the decline.

Q: What is your personal opinion?

A: Readers who will dream such dreams and can tolerate the resulting pain will come back. My hope and belief is literature will progress.

Back to Top

Research Publications

“Balivada Kantharao Navalalu Pariseelana“, PhD Thesis by Dr Yohan Babu, 1989

“Telugu Navalaku Velugu Rekhalu: Malapalli-Vamsadhaaralu“, Research Publication by Prof Yohan Babu